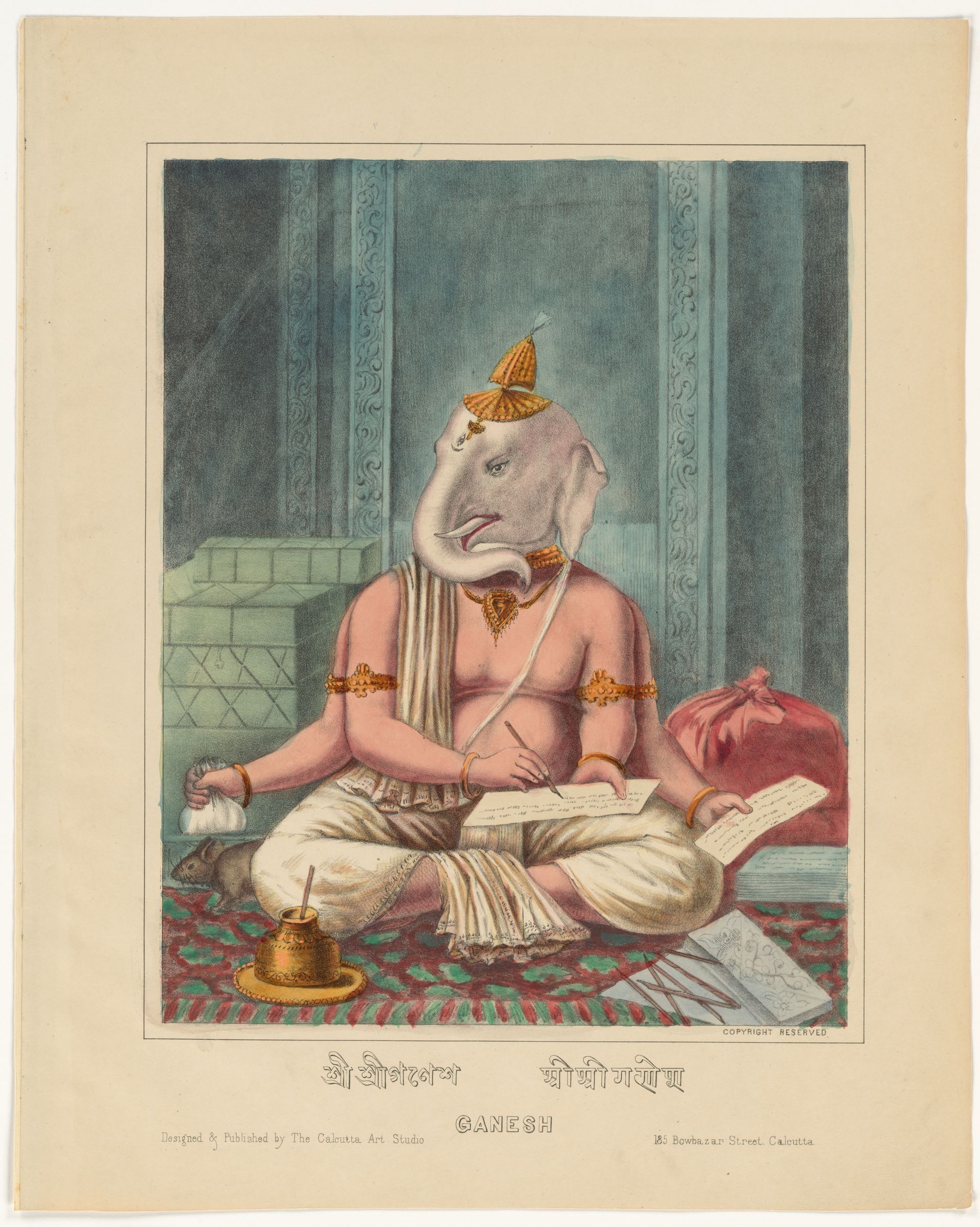

APOTHEOSIS | Sourav Sengupta

Poet & erudite Sourav Sengupta

SOURAV SENGUPTA is an Indian Poet from Kolkata.

Author of Aśoka at Dhauli, a metered treasure in 12 stanzas which narrates a seminal moment in the Asian subcontinent history, Sourav Sengupta will be the Apotheosis of our fifth issue in spring 2023.

In this last season’s episode, we discuss his wonderful poem, great books about poetry by Stephen Fry and James Fenton, the levels of abstraction every poet and artist need to know, how form follows function in architecture (and that includes poetry), Tagore the polymath,

and Krishna who needs no introduction.

How Aśoka at Dhauli came to be

MURIELLE MOBENGO: What a pleasure to have you. I wanted to congratulate you again for your beautiful poem. We had the chills reading it, and we loved every bit of it, the rhythm, the language, the story, everything was perfect. What was your inspiration for writing a poem like that?

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Thank you for your kind words. I am really thrilled that you like my poem on Ashoka. If you speak of inspiration, I guess I'm generally interested in history from an early age. History has been one of my favorite subjects. I've been reading history and I've been traveling all over the country visiting Indian archaeological sites. So this is one place that I also visited when I was a kid, which was the battlefield of Kalinga and we study about this particular event in our schools as well because it's a very transformational event for for the subcontinent.

If you look at the spread of the Buddha's message, Buddhism as a philosophy and a religion took off after the Emperor Ashoka fought the battle of Kalinga. After that, he developed this missionary zeal to spread here first of all and adopted that religion himself. So, Ashoka became a Buddhist and sent his children out as ambassadors out all over the world to spread the Buddha's message.

A lot of what India is known for today–Gandhi and nonviolence (ahimsa), cultural pluralism, tolerance, etc.–somehow links back to this event in my mind. This is where it all started. The national symbol of the national emblem of India is the four lions of Ashoka. So, in many ways, Ashoka and Kalinga are linked to Indian history and that is where my interest came from, and I thought I should write about it. This poem is written in something known as the ballad meter, a 14-syllable structure. A lot of Kipling's work is in that song and rhyme style. So, I looked at a lot of Indian poets also. Very few have written something on this subject in English. So, I thought, let me give it a shot and see how people respond to it. So, that's how the poem came about.

Poetry, subtle speech & the absence of self

In architecture, form follows function.

–Sourav Sengupta

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Wonderful. The level of poetic mastery in this poem is impressive. Because here in America–I think it's a global phenomenon–people forgot that poetry is a fine art. So it's supposed to be refined, and you're supposed to pay attention to the level of language in a poem. Poetry is a genre in its own right where musicality plays an important role. A poem without musicality and subtle speech is not a poem. It's prose.

Revue {R} has changed its editorial line because of Aśoka at Dhauli! We've decided we would publish poems like that only, because that's the beauty of poetry. I mean, if you don't have it, if you don't have that, then you have prose and people talking about their stories and whatever happened in their lives. Another wonderful thing about your poem is that you're not talking about yourself. It's not that we don't want to get to know you. Of course we do. This is why we're having this conversation. But the poem is about something elevating [we learn something reading it, our perception of life is augmented; new interests are kindled about the history of India, this warrior king. The poem is elevating; not centered around the Self.

Do you think that it's the poetic tradition of India which is very imbibed with mysticism that led you to write like that. Also, is it happening in India too? Are people "crushing" the genre of poetry and writing self-centered poetry-like prose only?

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Interesting. You talked about musicality being very important (rhyme, rhythm). These are the qualities we associate with poetry traditionally, in our mind. In fact, on a separate note, when I was sending out this poem, I was looking for publications to send this out. There are so many magazines out there, you would be surprised, maybe you already know. They clearly say that, "we don't want to have anything to do with rhyme, rhythm, musicality, that's not poetry in our definition." So that's a separate debate altogether. I was thrilled when Revue {R}évolution accepted this poem.

Coming back to India, I think that is a very distinct tradition, going back centuries of folk music, and folk poetry, which has inspired poets down the generations. India is a big country, a nation of nations, so to say. The part of India that I come from is Bengal, which is East. So, we speak Bengali, and we have a very well-rooted tradition of baul singers who are essentially wandering minstrels. They go from village to village with their stringed instrument, and sing and in exchange for their songs, they beg alms from the village folk, and that's how they survive.

Baul singers live very simple lives and sing deeply philosophical poetry with simple language of the day, a vocabulary rooted in the soil, highly relatable to the people. They would sing of profound truths about God, the oneness of all beings, the universe etc. So, that is the tradition.

We also had a tradition of Fisher folk in Bengal. Bengal is again a land of rivers. So the fishermen and the boatmen have their own tradition of folk music called Bhatiali ↗️in Bengali. If you look at some of the great Indian poets like Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam 👁, they have been deeply influenced by these folk traditions.

One of the most famous Baul in Bengal, historically famous is Lalon Fakir. Lalon is his name and Fakir is a generic surname attached to every Baul singer which essentially means "a poor man." So every Baul is known as XYZ Fakir. So, this excerpt is called

Sob Loke Koy Lalon Ki Jaat Sonsare," or Everyone asks of Lalon, "What is your religion in this world?" which translates like this:

What does religion look like?

I have never laid eyes on it.

Some wear malas around their necks.

Others with tabeez and so people say they've got different religions.

But do you bear the sign of your religion when you come or when you go?

–Lalon Fakir

Using very, very simple vocabulary and idioms, baul singers will convey something very hard hitting and profound and capture a universal truth. A lot of contemporary work is inspired [like that in India]; the music, the musical bands, rock, all the music coming out of India, Bengal, other parts of India, every part of India is inspired. Punjab, also, which is the Western part of India has its own tradition inspired by their own folk songs.

Sufi ↗️ of course has been influencing large parts of the world. Some thumbtacks of that inspiration, possibly may have crept into my work unconscious. Definitely not consciously.

Literary curiosity and Stephen Fry

MURIELLE MOBENGO: It's also the culture of India and beyond, the philosophy of oneness as you said. For me, poetry is deeply mystical. Of course, you can write about mundane things and whatever happens in life with a poem. But the purpose of poetry is introspection and if it does not get you closer to the inner truth, your own inner truth, the purpose of poetry is lost. How did you realize you were a poet?

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Well, I'm still not sure if I am in that sense, but I've been interested in literature and poetry from a very young age. I had a reading habit inculcated in me, particularly by my mother. So I used to read all sorts of things, I read all genres of books, fiction, nonfiction, poetry, etc, a lot of it in English. At some point of time, I felt that there are these great poems, which we all remember having either read them in our kindergarten or not. So, there is a certain quality to poetry which makes it very memorable. If you ask somebody to recollect what they've read, long back, they wouldn't be able to recollect lines from a novel. But they may be able to recollect some lines from a poem. So there is that kind of eternal quality in poetry that attracted me and I have been a reader for much longer.

Off late, I thought, let me try my hand at writing. So I came upon this book by Stephen Fry The Ode less travelled, ↗️. I like reading Stephen Fry otherwise, as well so I just happened to pick that book up because it was on the stalls, and it had Stephen Fry on it! I didn't know what it was about. But then I started reading it, I relaized he's trying to teach you how to write poetry. Isn't this what I was always looking for? Because they don't teach you how to write poetry in school, they only teach you how to read and analyze and paraphrase and explain the meanings and inner meanings and so on. But they never tell you how to write. They never teach you how to do that. The way Stephen Fry takes you through step by step, it makes it seem so easy, like a cakewalk. So that was the starting point. And thereafter, it was about picking up a theme or a subject here you like and start writing and then writing one more and more, and then you're getting better at it. So I would say I'm still in the early stages of this journey. Let's see where this goes.

They don't teach you how to write poetry in school, they only teach you how to read and analyze and paraphrase and explain the meanings and inner meanings of poems. But they never tell you how to write.

–Sourav Sengupta

MURIELLE MOBENGO: The early stages of your journey are awesome (laughs). That's a great beginning. In France, there's this tradition...I call them the sacred triad: Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, and Victor Hugo ↗️. What you described is true. At school, you are taught that poetry is basically these three guys, and some others, like Vigny and stuff [minor poets in comparison]. So, you have to live up to the expectations of their writing. Otherwise, you're not a poet. And at some point, I found that it was like a dictatorship or something. I thought, "Why? Why can I just just write my poems and be a poet?" But somehow, my own spiritual life led me to understand this.

I'm an initiate of Kashmir Shaivism, ↗️ a spiritual tradition based on master-disciple relationship (Guru-shishya), which means that you do not become a mystic like that. You have to be trained into that. I realized the same goes for poetry. You have to be trained into it. You need Masters you look up to otherwise, you're doing nonsense.

So, in the beginning, it was very, very difficult for me to accept that because everybody was busy doing something else. So the fact that you do not enter into poetry willy-nilly in France, and I suspect, a few European countries as well, like Germany, which has also a tradition of great poets (although the German language is more "cerebral"), Italy, is a good thing. You have to live up to the expectations of the masters before, the Dante, the Hölderlin, all these people.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: I would also recommend An Introduction to English poetry by James Fenton ↗️, along similar lines, like Stephen Fry, but Fry's is slightly thicker, so it takes a bit of time to get through it. But this one's also good.

I agree with what you're saying. After starting to write and getting into this thing of sending to journals, etc, for publishing, I realized poetry is being increasingly treated as something which does not require any training. It's no longer a craft, it's no longer art, it's no longer a skill that needs to be developed in the day. Maybe there is a merit to that thought that poetry is just an outpouring of what you're thinking about and any structure or any rules that you put around your writing inhibits that free flow. Hence, you should just write without thinking about any rules of the craft. But I personally don't subscribe to that. If you read a lot of the things you find on Instagram, you will wonder, "is this poem, or is this a quote? Or is this just a passing waste of thought? How do you categorize this? Literature? I think poetry is an art form. I was trained as an architect and we had this design professor who used to talk about these various levels of abstraction.

He would say that architecture is at relatively the lowest level of abstraction, because you can see it, there's a visual aspect to it, a tactile aspect you can feel and a spatial aspect you can roam around and experience. So the designer has so many tools to convey what he or she wants to convey. The next level or the next higher level of abstraction, he would say sculpture, because there's the visual aspect, and you may also feel the statue. The next level is painting, only visual aspects, so you only have the visual medium to communicate your thought. That is how much limited your tools become.

Now the highest level of abstraction for him is poetry, because you have neither the visual element, nor the tactile element, the touch-and-feel or experience element, and the spatial element is also missing. So all you have is a word through which you have to convey an image that makes the craft of the poet that much more difficult.

I wouldn't say "superior to any of the other". Each has is unique, but that makes it much more difficult and therefore it should by definition require a lot of training to be a poet. To be an architect, you need to train for five years in a design school or engineering school. But for poetry [the highest level of abstraction], there is no training...

MURIELLE MOBENGO: I agree.

On cursed poets & artists

MURIELLE MOBENGO: What do you think about the myth of the curse poet or artist, the cursed writer, the dark and the deep thinker into deep depression, not philosophical depth? People see writers like that.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Interesting how you put it! (laughs). In fact, it takes me back to my college days as an architecture student. We were in this campus in Kolkata. Engineering occupied one part of the campus and there was another end of the entire campus, where the arts faculty was housed, where you had students from philosophy, sociology, all the fine arts and humanities. And if you would stroll along, on an evening, towards that side of the campus, you would find typically the kind of creatures you describe. In Bengal, they'll have long beards, and they'll be smoking pot or something, and lying in some corner of the Villa or in some dark shaded area, wasting away their lives and so on.

It's not a stereotype. A lot of it is true because creativity–at least the kind of creativity that a poet or an artist espouses–is not very remunerative in our society. That's definitely true for Indians. So a lot of the creative people come from humble backgrounds, very simple families, or middle class homes.

Unless they have a backup in terms of some other skill, which can help them on their daily bread, it's very difficult to continue to survive as a purely creative person. I mean, how many of us can become that famous poet who will get invited to seminars and poetry readings and conferences? That is the unfortunate truth.

The situation, I would guess, is much better in the Western world where there is a greater appreciation of the fine arts and humanities in general. In India, even today, it could be a feature, a characteristic of the developing part of the world that the thrust of education is still on the STEM disciplines, that is science, technology, engineering and math.

So, most of the funding, the good jobs, the payback etc. goes to these disciplines. When somebody is studying Fine Arts literature, unless he or she has an inclination towards the academia and wants to become a professor, purely by selling your art, you can't really make a living unless you are blessed with some godfathers in that particular space. And that is where much of the depression and the gloominess comes from.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: That's a great explanation for this. About the situation being better in the Western world, I'm not sure. It looks better. But the West has created this awful, awful thing, which is the celebrity and fame, [I mean the business of entertainment in the West]. I have I wrote a tiny book about it.

I found out is that most of the singers and songwriters who are in the light right now, among these famous people, a lot of them are poets (a lot of them are also frauds, obviously) but a lot of them are poets. That's the only thing that's left for you in the West if you love language and music and you don't know exactly why but you feel that it's your calling. The academia is somehow inaccessible for a lot of us because poets seek freedom. Universities are very traditional so it's hard for a poet to thrive as an academic.

Now your options are some kind of 9 to 5 but because poetry is a calling, and is deeply existential in nature, you may destroy yourself little by little or your creativity will become dimmer and dimmer, and that's it. So, you go for it and you want the stage, and suddenly turn into a pop star and people "love" you, and then it's so stupid because this whole machine crushes you, and now you start doing drugs, now you start destroying yourself with all kinds of irresponsible behaviors. So I think the West has found a putrid way of dealing with poets.

Either you want to make it and you become famous, or you don't, and, to hell with you. Human societies are definitely not made for us. The same goes for artists. I often say that poets and artists are one. They're just experiencing creativity and, and the quest for oneness at different stages of their journey. But it's the same thing. So, if you want to become an artist, what will happen to you? No one will care, unless you come from a wealthy family and you can do some kind of fine art school and find a godfather or a patron to support you. But otherwise, it's very, very difficult. So we just lose it.

The question of sponsorship & Instagram poets

SOURAV SENGUPTA: You know, Murielle, in this hankering or struggle for fame, a lot of artists are just falling by the wayside. I think sponsorship is a big issue. Because if you look at the Golden Age of poetry, at least, if you look at the history of India, you would have these court musicians and court poets who would be associated with these Rajas and Maharajas. Renown poets like Mirza Ghalib ↗️ came up purely because of royal patronage. They really didn't have to think about where their next square meal would come from; the king would pay for that. They just needed to be in court and compose a few lines for the king.

Even Hindustani classical music, which is the ancient Indian tradition of music, also flourished in that form, because we have these Karanas of music. Each Karana represents in some way the court of some particular king. But in contemporary times, of course, these kingdoms and these rajas and maharajas and patrons have withered away. Modern governments have many different priorities, particularly if you look at a country like India, patronizing art, patronizing poetry is possibly very low on their priority list.

I'm not saying that they don't do anything to support the arts. But of course, every artist now is on his own to search either for a godfather and it's a jungle all the way up if you can make it to the pyramid, and it's very competitive. When you are singer, getting a break in Bollywood, which is our version of Hollywood, so to say, the Hindi film industry...I mean, there are so many talented singers out there. Well trained and really, really talented. But how many of them make it? You hear such horror stories of what people need to go through, what kind of favors, dark and dingy stuff.

So that is the unfortunate reality. Some of it may be true for poets as well. I mean, unless you're commercially successful. Being a commercially successful poet is great; everybody is hankering to publish you no matter what you write. Right? There are so many examples like Instagram poets who get published while some do such great work and doesn't.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Instagram poets are usually people who have not been trained into poetry or even the basics of it. I remember when I was on social media, they were referring to poetry as word vomiting.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Or verbal diarrhea. That is another.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Yes. How awful. I kept wondering, my God, do you realize what you are saying? There is nothing beautiful in vomiting. You are obviously not well and you need a cure. Poetry is supposed to elevate, to conjure clarity and beauty in the transcendental sense. So-called Instagram poets are using poetry simply to unburden themselves with all the negativity and the depression.

Obviously, this leads to very bad poetry and also very aggressive poetry. Who wants aggression, especially from total strangers? Why such stupidity? I understand that their writings express the level of pain they are into, but the fact that poets are not trained into poetry is a huge, huge problem. I created Revue {R}évolution to address this problem in a subtle way. Now we’re becoming less subtle since we have online courses. I didn’t want to offend anyone, but I wanted to remind people what poetry is.

Sure, life is difficult but I mean, life is difficult for everyone, not only for poets. You have to get over it at some point (laughs) and not walk around insulting strangers (and editors) in free verse! Human life is a struggle and you have to find why this is happening to you and be brave about it and live your life. I get carried away with that subject because the problem of Instagram poets deserves our attention. Instagram poets prevent talented poets from being seen.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: The publishing industry as far as poetry is concerned, is also publishing poets on Instagram who have more followers. So the criteria for getting published is not necessarily about good quality of work. But what are the chances that this particular book will sell because x y z poet has more followers than another one who maybe writes great stuff, a very well trained, profound poet, but has no followers? Also, on the point you made about this verbal vomiting, that other book by James Fenton talks about this.

Fenton compares it with music and says the same poets, the same people who extol the virtues of this kind of poetry when it comes to their taste in music, will they ever listen to a song that is out of tune or really bad? They will not. So you do not hold poetry to the same standards apparently. You can still do your distressing and catharsis using music, but if it is bad music, if it is cacophony, if it is out of tune, if it makes no sense if there is no rhythm in it, then you are not going to enjoy it, right? So why should not poetry have the same standards?

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Very interesting point. Besides the formal training as a poet, there is also a problem of existential training. From what I am able to see–we no longer receive Instagram poetry because now the editorial line of the review is very, very clear. You are not going to submit to a Revue {R} if you are an Instagram poet–but we still receive a lot of poems like that, the angry stuff and word vomiting and absence of structure. So, there’s the literary training and there’s also the existential training. It is like poets do not want life to teach them anymore!

Poetry is existential, deeply spiritual, deeply philosophical, and if you do not want existence to train you, you will never be a poet. You can label yourself all you want. But ultimately the Divine, Life, or the Absolute–whatever you want to call it–trains poets. So without humility, this humble attitude towards the enigma of existence, towards your own self, all attempts at poetry are vain.

You think you know who you are, you think you are those emotions you write about and identify with but are you interested in the truth? Are you interested in finding out what's beyond that anger you so cherished or that lust you live by or that sadness which, according to your perception, constitute you? What if you were completely other? If you do not have the courage to question your identity, why would you even begin to write poetry in the 1st place? By the way, Sourav, what happens to your emotions in writing?

On emotions, the craft, and Harmony

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Emotions are a very important part of the creative process and the best way to deal with emotion is to transform it into your work so that it is reflected into your work. At the same time, if your work is purely a kind of download of your emotions or feelings in the here and now, which may not have any relevance to anybody else in the world, then that is not good poetry, right?

Good writing is deeply moving. When you feel this poet is talking about how she felt after a breakup or something else and how she dealt with it, that is well and good but a lot of people go through it. That is part of life, we deal with it. So what is she trying to talk about? Is there a bigger story that you are telling people? Is there a higher truth that you are speaking to through your work, through your emotions? That makes all the difference.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Sourav, when do you know how to stop when you are writing a poem?

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Knowing when to stop comes partly from your approaching poetry in the classical sense, that is, trying to write in a particular form which will a set of boundaries to your writing. Free verse champions would say that boundaries are bad, break apart all boundaries, it is a free world and all of that, but I think these boundaries, these little frameworks of fences that you put around your work, whether in terms of meter, length, number of word syllables, or lines, etc. help channelize your creativity, at least in in my case.

It helps me to channelize my thought and creativity with conditions, parameters. These are the extent which I can write, and I have to tell what I want to tell the reader within these many words or syllables. Ashoka is of course a much longer poem because the subject demanded longer, but a lot of the poetry I started writing was sonnets because I found that, these are the perfect form in the sense that you have to stay within 14 lines and within those 14 lines, I think you get enough play or flexibility to express one emotion or one thought and also enable the reader to reflect. Knowing when to stop in that context is obvious.

Also in that case, once you have conveyed the gist of the story, you just stop. Aśoka is a narrative poem so the narrative obviously came to an end in its course. You can still go back and see if you have said all that you needed to say beyond the narrative or the facts that you wanted to talk about, and that is when you know when to stop.

Possibly some of it also comes from my training in architecture where form follows function. Boundaries condition the functions of the spaces you design. Whatever takes your fancy as a designer, you have to ensure that this activity needs to be served. If you are designing an auditorium, it needs to seat so many people, it has to have these many facilities, these different types of rooms, and this is the space available to you, you do not have an infinite amount of land. So from those boundaries, conditions come and determine the creative aspects of your work, which makes architecture so much more interesting.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: You just reminded me of something I read about Sri Aurobindo. One of his disciples was asking a question about freedom; somehow he wanted to be free and felt he wasn’t free so he was complaining about that saying “I want to free” and Aurobindo asked him, “but why do you want freedom?” (laughs) which I think was wonderful and a great question to ask poets as well and free verse champions; that freedom, why do you want it?

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Since I have this book by Stephen Fry in front of me, there is one line in his introductory chapter where he is discussing exactly the same issue that we are talking about, free verse and structure. So here it is:

Mankind can live free in a society hemmed in by laws, but we have yet to find a historical example of mankind living free in lawless anarchy. –Stephen Fry

So, what Fry is saying is if you want freedom, the prerequisite is structure. There cannot be any freedom without structure.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Very insightful. The question of freedom is tacky. In the beginning, we were receiving a lot of free verse and it was difficult to move away from that. I knew I wanted to move away from that, but this was the core of our submissions. Some of them were interesting from a logical perspective and others from a narrative perspective because America loves a good story. So everything that you write has to be some kind of a story. So, it was difficult for me to find a piece that went beyond the story (poets who submit to Revue {R}évolution are mostly Americans).

So, if it is just a story about you and it is not rhyming, there’s no metrics, then you do not need to write about it, or submit it to an editor for that matter. Why not talk to a friend? There’s no structure and even the story suffers from that because it makes no sense. "I had a cat and then my cat died and then I got depressed and then I said, I want to write a poem about it, but I can’t" (true story. I received something like that) or "I used to be a CEO in this major company and when I lost my job, I realized that poetry was my calling." I mean…There’s your freedom. But for what? Because apparently, once you have it, it’s just anarchy.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: In fact, sometimes, you are reading these “I have a cat and the cat died and then I looked out of the window and there was a dog and etc,” then you start wondering once you’ve finished reading the poem, “Am I foolish? Because I did not understand what this was about.”

MURIELLE MOBENGO: Yes! The silent member of the editorial team and our patron is a mathematician. When I read these stories to him, he has the same reaction.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: This is sadly true and if you look at some of these famous poetry publications and journals which are supposed to be the gold standard in poetry at least, more than 90 % of what they publish is along these lines. Maybe there is some profound truth to that kind of poetry, which some of us like you and I are yet to approach that level of transcendence where we can interpret and appreciate, but really…This attitude of saying that everything that has come before is jelly, not poetry, and we are going to define poetry by saying that poetry is something which is not these things is negative definition. So, what is their definition of poetry? Then if you look at the submission guidelines in some of these websites, they say it cannot have form, it cannot have meter, it cannot have rhyme, it cannot be in a traditional form, it cannot be X, Y, Z, but what can it be instead? What can it be? I mean, what is your definition of poetry?

Maybe this is also like fashion, you know. These things come and go. There are good websites and platforms which promote meaningful poetry. Not to sound elitist or something, but if the kind of poetry that you publish is not memorable, if somebody cannot recollect after reading at least one or 2 lines, then what was it about?

MURIELLE MOBENGO: I agree.

Polymathy, Tagore, and poets

MURIELLE MOBENGO: I had a dream when I was 19 years old. I wanted to create a literary review like the Romantics in the 19th century, a vivid century in Europe in terms of literary creation. Literature was really good, poetry was really good and for me, it seems like we are on a downward spiral since the Industrial Revolution, because people are now obsessed with matter and the desire to control it. So, poetry suffered from that, art too. So I wanted to create a review in this tradition of these highly romantic and highly learned poets from the 19th century, in French we would say “une revue savante de poésie.”

I have also observed that poets are usually extremely talented. You are proof of that yourself; you are an architect, you have been trained in architecture; there is a lot of philosophical depth also in your poetry. Being a poet, you are obviously an artist, you simply do not need canvas anymore. Your craft has been refined to such a level that you do not need pigments and brushes anymore since you are able to conjure images with the mind, with the word.

Do you think that being a poet is connected or linked to edition and and, you know, being a polymath, which is the equivalent of in in America, everybody talks about polymaths, so that is fine, I am using the word, but do you think that there is a link between being a poet and being extremely gifted.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: There is possibly some link because if you again, if I were to look at in my immediate context from the place where I come from, we have all heard of Rabindranath Tagore. Most of the people in the West know him for his collection of poems, The Gitanjali, which gave him the Nobel Prize. Like you said, he was a polymath. He was a painter, an artist, a songwriter, a playwright, a novelist, a short story writer.

He founded a university on his principles of reviving ancient gurukul system of learning, so in that sense, he was an educationist and a nation builder as well, and he had a great interest in science. He met with Albert Einstein, and they had this famous dialogue and wrote a book of popular science which proves the extent of his erudition! It is called An Introduction to the Universe ↗️, where he talks about his understanding of comets and galaxies and planets and solar systems and all of that.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: I did not know that.

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Tagore inscribed that book to a person called Satyendra Nath Bose, who was another scientist, a contemporary of Einstein. Tagore was such a fascinating person. A lot of great poets have been polymaths, at least they have had a diverse set of interests. There are so many examples.

But is it a prerequisite to being a good poet? Maybe not? There are an equal number of examples where a poet has been only a poet possibly and not many other things, but if you have a diverse set of interests about what is happening around you in a diverse set of fields or subjects, I think that informs your creative work. Your writing is sensitive and of greater value to the reader as you are bringing not only your expertise as a poet, as a craftsman of poetry, but you are also bringing your knowledge of so many other things into your writing, which makes your writing timeless, and unique.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: My intuition about that is that poetry leads you to that. You can be a regular dude writing poetry but because you are working with language which is the basic element of consciousness, your intellect would want to venture at some point in all kinds of intellectual disciplines, from science to music to art to philosophy and so forth.

I admire poets a lot myself, for their intellectual flexibility and versatility, the interest in various subjects and most of all, their interest in what it means to be human. All the wealth in poetry comes from that, and maybe from another dimension.

What a lovely conversation. I have one last question. Who is your favorite mythology archetype, or symbol?

On Krishna, the many colors of the human soul and the Mahabarata

SOURAV SENGUPTA: Well, that is a tough question. I would I would say since you talk about mythology, if I can go back to the the Indian epics, The Mahabarata ↗️, one of the 2 great epics in the Indian tradition, the other being Ramayana ↗️, I would say my archetype would be Krishna because he is a God, essentially. He is supposed to be a Divine being who is placed into that story in human form, but he is not your typical God because of his character and if you were to study the Mahabarata with today's lens, you would possibly characterize him as a villain because he is scheming, he is cunning.

He uses all sorts of devices to get his way through, change the course of events, change the course of the war that is being fought. But at the end of the day, when he asks this very idealistic character called Arjuna, his protégé, his disciple, to pull a fast one on someone, Arjuna is puzzled and wonders, “how can you advise me to do that? This is not idealistic, this is not ethical, how can I do that? What about karma and moral?”

Then Krishna, this is a typical characteristic, smiles and sniggers and responds: “I am God, so whatever I say is right, that is rule number one. And rule number two is, refer back to rule number one (laughs). So at the end of the day, everything that you do as long as the ends are noble, the means are justified. That is his mantra in a sense.

Even if you do not have to take the straight line with meander here and there, as long as the road takes you to the right destination, take the road. So it is an interesting character, and I would say there is a lot to learn from the way he is portrayed in the epics, because the various shades of human character really come out.

If you look at some of the Western epics, so to say, there are very plain characters, either pure evil or purely devious*** or pure but Krishna is somebody who has many shades to his character and you

cannot really put him in a box. I think that that is what that is what humanity is about. Nobody can be put in a box. You respond to situations. You sometimes need to be good, you sometimes need to be bad. Even though you know something is right, you need to do it wrong. So, Krishna would be my archetype from mythology.

MURIELLE MOBENGO: That is a wonderful answer, my God. Thank you, Sourav.

*** Norse mythology is a beautiful exception. For example, All-Father Odin, the God of gods and dispenser of Poetry (Skald), is mesmerizing and shady. So does his brother/son, the infamous and charming Loki, who torments the purely good, among which Thor, god of thunder (light). We will prepare a complete issue on Norse mythology and its connection with Hindu myth soon. In the meantime, this article on the origins of poetry will help.

Advice to a young Artist, Rilke style

From my own personal experience, I’d say, if you want to be a good poet, a successful poet, you definitely need to read more poetry.

Read the great masters in poetry, and certainly do not have this attitude that “I know all and my thoughts and feelings are the ultimate guide for my poetry and I do not need anybody else to tell me that.” Poetry is a craft, it needs to be learned.

You can bring your own style in writing, but at least know what has come before you, and if you read more poetry, you will understand the various ways in which people have expressed thoughts, ideas, and emotions through poetry so that will give you a greater bandwidth, so to speak, when you start writing yourself.

For me, poetry is still like a hobby which is possibly evolving into something more because I have a separate day job which is different from writing poetry. So, my next advice is, do not rely on poetry. Build a different skill set which can help you through life because it is a difficult journey.

Cultivate that hobby, evolve it into something more than a hobby.

–Sourav Sengupta

Comment this interview on YouTube!

Be courteous & relevant. Thank you.

Revue {R}évolution